Are you trying to slay the dragon of completing a novel or of getting a nonfiction book published? Then learn why April 23 is a day to celebrate books — and how it became UNESCO’S World Book and Copyright Day, which honors the book publishing process.

“Day of the Book” backstory — Saint George and the dragon

Since the Middle Ages, April 23 has been celebrated as St. George’s Day in many countries. “Sant Jordi” is the patron saint of the Catalonia region of Spain, and the celebration of “La Diada de Sant Jordi” in Barcelona and the other Catalan provinces is at the root of The Day of the Book.

Saint George was a Roman soldier who converted to Christianity and — tradition holds — died on April 23, martyred for this faith. Centuries later, during the Middle Ages and at the beginning of the chivalrous tradition, soldiers coming back from the Crusades also brought back the romantic legend of St. George slaying a dragon.

According to the story, a ferocious dragon terrorized a town, demanding that the inhabitants sacrifice two sheep a day to keep him fed. Once the sheep were gone, the townspeople were forced to sacrifice their children, chosen each day by lottery.

The king’s daughter lost the lottery and was awaiting being devoured by the dragon when Saint George happened into the town and slew the beast with his sword. The dragon’s blood spilled to the ground; on that spot a rosebush instantaneously grew. Saint George plucked a rose and gave it to the princess.

According to a Barcelona tourism site, “Records tracing back to the fifteenth century describe a rose fair being held for Sant Jordi that was traditionally visited by engaged couples.” So for centuries, a man’s gift of a rose to his girlfriend was the accepted form of celebration of Saint George’s Day on April 23, sometimes called “Day of the Rose” or “Day of the Lovers.”

A day for lovers becomes a brilliant book promotion

Some sources credit a Catalonian bookseller for noting that April 23 was also the date of both William Shakespeare’s and Miguel Cervantes’s deaths (both in 1616). During the 1929 International Exposition, book stalls were set up. Then, in an an enterprising stroke of book promotion, it was determined that a book would be the perfect gift to be given in exchange for the rose, and the mash-up of flowers and literature — El dia de Libre, the Day of the Book — was established.

[In the detail of 1470 painting by Paolo Uccello at the top of this post (National Gallery, London), the princess, saved, holds out her hand as if to say, “Nevermind the rose – where’s my book, St. George?”]

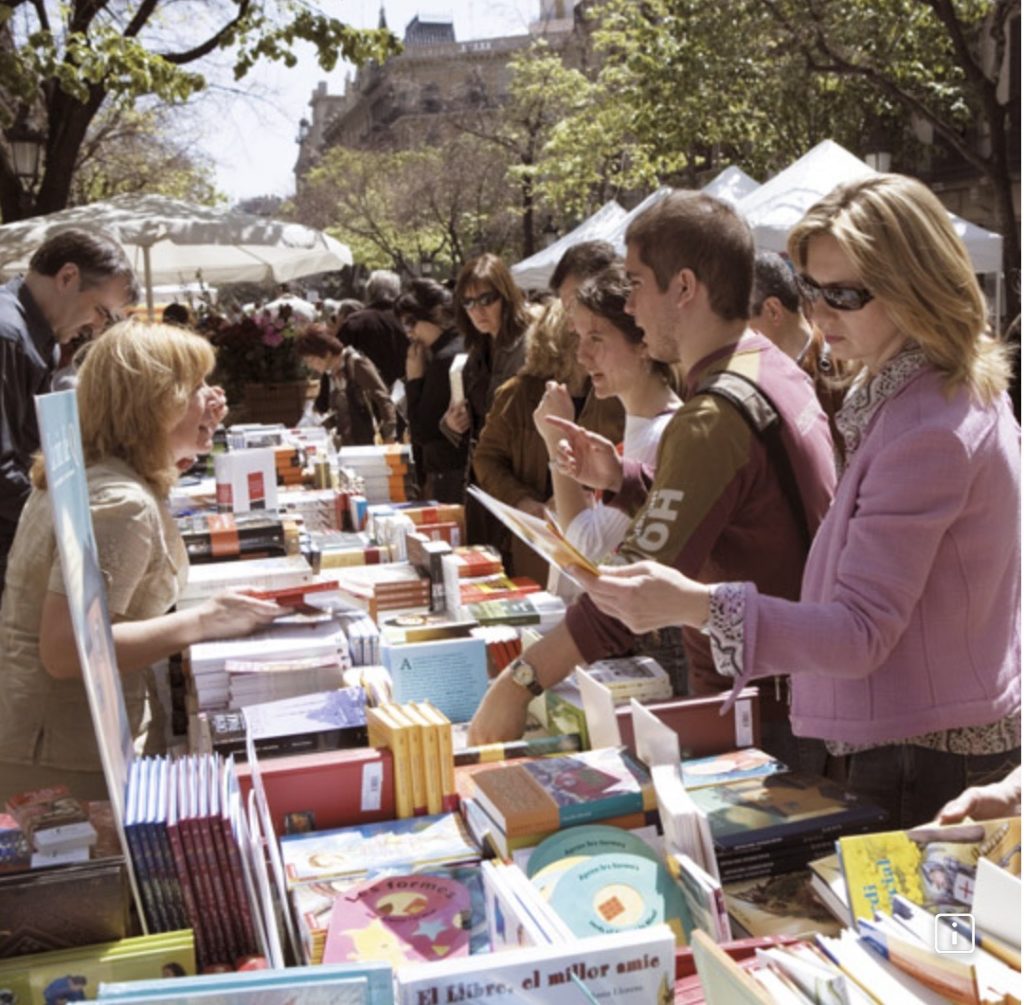

Today, the El dia de Libre tradition is firmly entrenched in Catalonia and books are exchanged for roses and vice versa, regardless of sex — “a rose for love and a book forever.” On April 23 in Barcelona, Spain’s publishing capital for books in both the Catalan and Spanish languages, the annual Book and Rose Fair is held. Along the famous, tree-lined pedestrian thoroughfare, Las Ramblas, hundreds of stalls are filled with florists and booksellers.

Some sources estimate that nearly half a million roses are sold and it is estimated that half of all annual book purchases in Catalonia are made on April 23. Other literary events, such as author readings, also take place and the date is also a popular one for launching new books into the marketplace. It is also the day each year that the Miguel de Cervantes Prize, Spain’s most important literary honor, is awarded in Madrid.

UNESCO’s World Book and Copyright Day

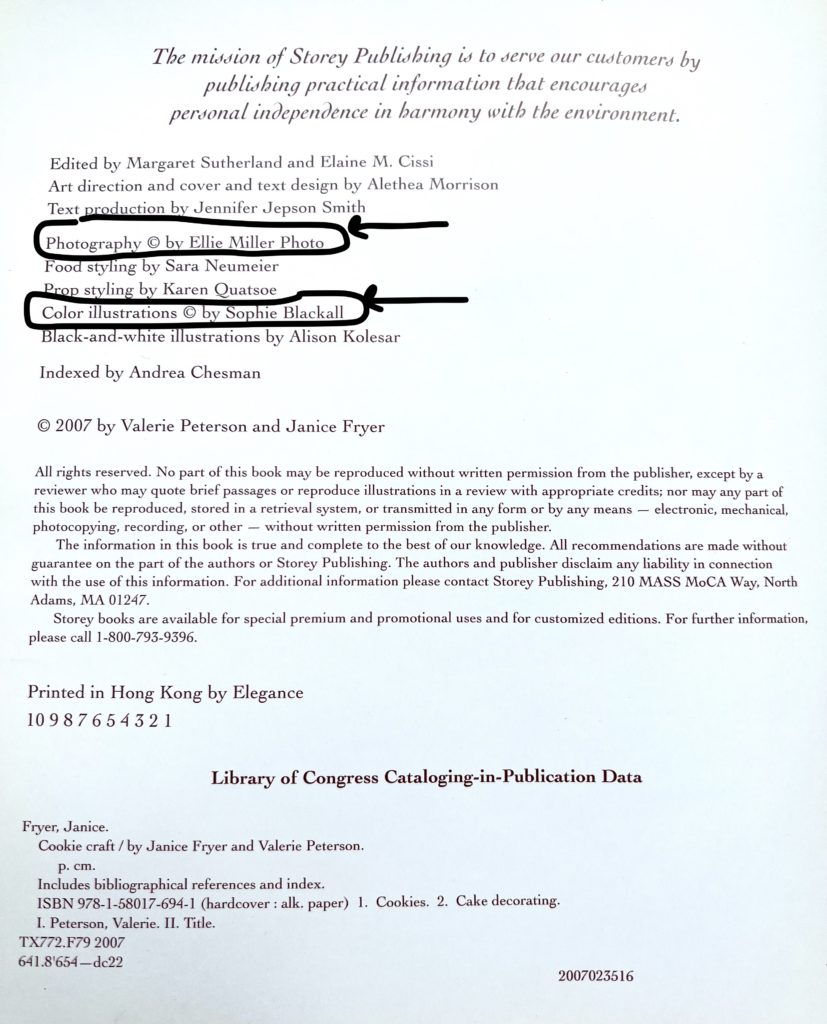

Inspired by the Catalan El dia del Libre, in 1995 The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared April 23 to be World Book and Copyright Day. The goal of World Book and Copyright Day is to promote reading, publishing, and — critically important — the protection of intellectual property through copyright around the world.

UNESCO encourages the support of authors, publishers, teachers, librarians, and the media to help bring the World Book and Copyright Day celebration of books to the greater reading public. Each year, UNESCO names a city as the World Book Capital, and the selected city organizes literary events around a theme, such as” books and translations”, or “the link between publishing and human rights.”

The U.K. and Ireland celebrate World Book Night on the evening on April 23. The annual event is run by The Reading Agency, a national charity that “tackles life’s big challenges through the proven power of reading.” Note that since the mid-1990s, the Reading Agency has promoted children’s books and reading by giving kids a token that is to be exchanged for a book. Due to the late April conflict with the U.K. and Ireland school calendars, this children’s event — World Book Day — takes place in those countries on the first Thursday in March.

Of course, copyright is critical to a creator’s career — a sword that protects the value of the soul, wings, flight and life we produce for the entertainment and edification of others.

So if you’re on a publishing journey, when you celebrate St. George’s Day (as I know now you will), think of both of centuries of book love and the valor of copyright protections.

“A rose for love and a book forever.”